I recently had the pleasure of talking with one of the world’s biggest hit songwriters, a gentlemen named Even Stevens. (Awesome name, right?) When I was growing up, back when I was a kid listening to my parent’s radio station of choice, I heard some of his hits hundreds of times. There was Eddie Rabbit’s “I Love A Rainy Night,” “Suspicions,” and “Drivin’ My Life Away.” There was Dr. Hook’s “When You’re In Love With A Beautiful Woman.” Kenny Roger’s “Love Will Turn You Around.” And plenty of others. He’s had dozens of hits and won just about every award that a songwriter can possibly win. I could sit here and list two dozen of them. Just as I could list fifty hit songs he’s had. But the ones mentioned above are all songs I’d hear on my parents’ radio station and enjoy. And I was always picky and strongly disliked half the stuff on the radio. But those songs were favorites. I believe I even had my mother buy some of the albums those songs were from on 8 Tracks. Obviously, at the time I had no idea that the same person was writing these songs but he was. And he’s still a hit songwriter today. Some of his recent credits include Tim McGraw’s “Carry On,” Trace Adkins’s “When I Stop Loving You,” and Kenny Chesney’s “Round and Round.” Suffice to say that at some point you’ve heard and loved something he’s written. So, sit back, relax, and get to know the guy, who, it turns out, is pretty darn cool.

https://youtu.be/ebt0BR5wHYs

MM: Your book is published by Heritage Builders. Did you have an easy time finding a publisher?

ES: I had a very easy time, actually. Usually that’s the nightmare of getting a book published and he [publisher Sherman Smith] actually was in an audience when I was performing at a thing with the lead singer of Alabama [Randy Owens] down in Muscle Shoals. He had just published the Rick Hall Muscle Shoals book and he was sitting in the audience with Rick and afterward he came up to me in the hotel at about one o’clock in the morning and said “I want to do a book on you.” And I’d already had my book started – I had been writing on it for about five years – and I said, well, if we can make a deal, that’d be great. And that was how I found my publisher. It was perfect. Because I have friends who are still looking for books and they’ve had twenty rejections.

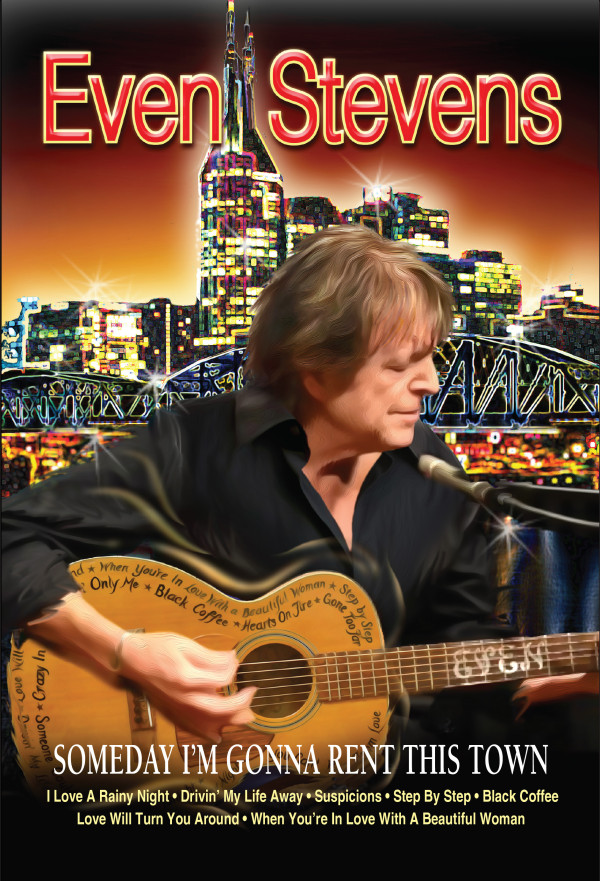

MM: What’s the story behind the title? Why Someday I’m Gonna Rent This Town as opposed to Someday I’m Gonna Own This Town?

ES: Well, there’s an old joke. It’s about a country boy who tries to go to New York City and make it and he goes to New York City on a bus and gets there in Times Square with his bags and he sits his bags down and he looks up at the skyline and he says, “Someday I’m Gonna Own This Town!” And he looks down and his bags are gone. And so I always do that old joke and I thought it was a good turn on that.

MM: Will you be doing a book tour to promote the book at all?

ES: Yes, I actually have been traveling quite a bit. I’ve done some book signings here at the Country Music Hall of Fame in Nashville. I’ve done about five book signings so far. I’m going to Burlington, Vermont soon and I play a lot of private and songwriter festivals and in May I’m gonna do two book signings and private concerts down in Key West. The Key West Festival that I do every year. And I’m going to Virginia, too, I think, with Richard Lee. He’s a great songwriter. I’m going up there and I’ll probably be doing a book signing. So, I’m kind of tying in my book signings with gigs wherever I play.

MM: You just started doing the live performances not too long ago, right?

ES: That’s right. Probably seven or eight years ago, maybe by now it’s been that long. When I came to Nashville, I played every chance I could. I kind of lived off that. When I started having some hits [with songwriting] I quit doing it because I was so busy at doing those things, getting songs cut and recorded and everything. I just quit playing live. Really, I did that for two or three years really steady. So, I just fell out of doing it just because I was busy and for about twenty years I didn’t do it. And my friend Paul Overstreet – he’s a great songwriter, he wrote almost all the Randy Travis’ big hits and Blake Shelton and some different things – he wrote “Some Beach” by Blake Shelton – he called me one day and said, “I”m doing my yearly benefit for St. Jude’s down in Biloxi, Mississippi that I do at the Hard Rock Theatre and would you come down and play some of your hits?” I went, “Nah, nobody really cares about that.” And he goes, “Oh, no, you need to come do it.” So, he talked me into it and I got hooked. [Both laugh] So, now I do it all the time. Every chance I get, I love to go out and play. It’s great, too. People know the songs and they sing along.

MM: Do you do most of your big hits then?

ES: Yeah, mostly. I throw in some new stuff, too. But, you know, when people really know like “I Love A Rainy Night,” “Drivin’ My Life Away” and “When You’re in Love with A Beautiful Woman” and “Love Will Turn You Around” they know those songs and they really enjoy them, you know?

MM: When you write songs, do you prefer writing alone or with co-writers? I know you do a lot of co-writes.

ES: I do. I co-write quite a bit. Now, like “When You’re in Love with A Beautiful Woman” I wrote by myself and that was based on a real experience. “Crazy in Love,” I did co-write that with a keyboard player named Randy McCormick. I wrote those words and I had the song kind of written and I wanted to get a little different slant on the chord progression in it, so I teamed up with Randy and he put some different chords in there that I wouldn’t have normally gone to I guess. I did co-write that one but I did write all the words to that one. I pretty much had it laid out. I like to co-write because it’s like a party and it’s fun. And I had such great experiences writing with Eddie Rabbitt for so long. We wrote over 900 songs together. And it was always a great experience doing it because you come up with something that you really wouldn’t come up with by yourself possibly. The best of both worlds gets in there and it’s exciting because things happen that you wouldn’t expect, if you were writing it by yourself.

MM: Are you still doing co-writes today or are you writing alone? Or have you stopped writing?

ES: Oh, no. I write continually. A lot of guys write from 8 to 5 like a job and have great success with that. I know some guys who write that way. But I’ve never done it that way. I just write when I feel it. When I get inspiration to write a song, I write a song. I might take ten minutes doing it or it might take a month. But whatever it takes, that’s the way I look at songwriting. Whatever it takes to make it great. Sometimes I go for three or four weeks and don’t write anything and then all of a sudden I’m in my studio for weeks working. I have some other interests, too. I paint. I fish. And I’ve got a family and stuff. So, I never worry about going dry or anything. If I’m not inspired I just go do other things and let it come when it comes. And I really feel like I’m doing my best when I’m inspired. I really do like co-writing though. I like just being with my buddies.

MM: In 1978 you began officially producing records. Did you just gradually learn from all your days in the studio or did you have a mentor in that department?

ES: Well my mentor in songwriting, and the publisher I teamed up with, finally, Jim Malloy, that I speak about in the book, he also was a great engineer and producer. He produced “Help Me Make It Through The Night” by Sammi Smith and had a Grammy winner with that one and other songs. But he was really known as an engineer and I really learned a lot from him. I just picked his brain all I could in the studio. About how to get the right sounds and everything. How to get a real good sound. And I guess from just doing demos and everything I started picking it up. And I engineer somewhat, too. And things just kind of fell in my lap with people wanting me to produce them because they liked the way my demos sounded. And so I kind of fell into it, you know?

MM: How old were you when you learned to play an instrument?

ES: Well, my dad and sister had a gospel group – a local gospel group – and they played a bunch and I learned guitar. He had a four string Tenor guitar sitting around the house that he just bought because it was pretty, I think, and I kind of learned to play on that guitar. And to this day, I fret the guitar incorrectly. People will say, I don’t know why you set that chord that way and it’s because I learned on a four string and when I got a six string my fingers went the other way, which is a little different. I played a little with them, gospel songs, but that wasn’t my forte. I wasn’t enthralled with that. When I was maybe 11 or 12 I started doing that. So, I always had a guitar and just over the years I learned to play. In Nashville, there are people that are really unbelievable guitar players. I don’t consider myself one of those. I just play guitar. There are just people that know so much about how to play guitar and are so great.

MM: Did you have somebody who taught you the chords and chord progressions or was that all self-taught?

ES: No, I’ve never taken a lesson. I just kind of worked it out.

MM: Kind of from the beginning you wanted other people to sing your songs. It was only a bit later that you started trying to be a singer, too, right?

ES: Yeah. Well, I played in some clubs in New York when I was there in the Coast Guard and also in California. I played other people’s songs and threw in some of mine when I was writing them to experiment. Well, you sang then and you’d better be good or you’d get booed off the stage. So, I got better I guess. I came to Nashville and I wanted a deal where I was a singer and a songwriter. And I turned down some things. I turned down a writing deal with Ray Stevens, that I worked for for a little bit, because he didn’t have time to produce me. He wanted me to be a writer though. And I turned that down because I said I was looking for an artist deal and then when I got it and had an album out I didn’t like the lifestyle. I had been out on the road to promote it and I really didn’t enjoy being gone all the time. And not writing songs because I was too busy traveling and stuff. I just called up the label head and said I just really don’t want to do this anymore. I was out on the road for about two months or so. And I said I just want to go back to being a songwriter. And he said, “Well, I never got that call before.” And I did. And I was so happy to do that. But I think I’d still be wondering if I should have been an artist if I hadn’t tried it.

https://youtu.be/uZwaYsoOk2Y

MM: That was Elektra and your album A Thorn on the Rose, right?

ES: Yes, it was. I made that album with Shel Silverstein.

MM: Now that all these years have gone by, do you ever regret not making a second album?

ES: No. Actually, I just made an album that the CD is being pressed now because people ask me to sell CDs on the road. So, I finally put one together. So, I’m actually doing that. I don’t really care about it being a hit on the radio or anything though. I just want to sell it to my fans.

MM: Are you self-releasing it then?

ES: Yeah.

MM: Is it gonna be on Amazon?

ES: I don’t know what I’m gonna do with it. I haven’t thought about putting it on Amazon. I imagine it’ll be on iTunes or something. But I’m really doing it to sell on the gigs I play.

MM: When you started out songwriting, were writers paid royalties back then or was it just a flat rate for the songs?

ES: Well, there’s two ways that songwriters get paid. One is mechanical royalties, which is the sale of CDs. Cassettes. Vinyl back then. Anything that you can put in your hands. Those you get paid from the record labels directly from them. Actually, they pay the publisher and the publisher has to pay you. So, that’s one way you make money as a songwriter. The other way is you get airplay. For on radio, TV, films, clubs, different places. And that’s collected by BMI and ASCAP and SESAC, the collection agencies. And that’s paid directly to you for the airplay that it gets on those things. So, that’s always been the case. Now the rate has gone up gradually for songwriters. When I first started for an airplay on radio it was like five cents, I think. Now it’s up around ten cents. So, it does go up. It hasn’t gone up as much as we want it to but it has gone up. But the thing we have a problem with now is the rate that we get paid for online pay.

MM: Streaming?

ES: Yeah. Because the copyright laws have never been changed and never addressed that, so they just made up their own rules. Spotify and Pandora and all those. They just made up their own rates. Instead of ten cents a play it’s like one one hundredth of a cent. So, we’re trying to change that. With the songwriters association I’ve been to Washing DC to talk. Last time I talked to 15 senators in their offices about getting on board with some legislation, trying to get it so it’s more fair. More in line with what the rate is for other things that have been addressed, you know? The copyright law hasn’t been changed since ’76, I think it was. So, it’s just not good that it hasn’t been changed because people are taking advantage of it because there’s no law that says what they have to do.

MM: It’s almost like they take your songs prisoner and then they tell you what they’re going to do with them.

ES: That’s what they do. I mean, we like it being played online and people buying it that way. We just want a fair rate.

MM: When I looked up some of the songs that you’ve written on Spotify there were some instances where I couldn’t find the original versions but they had karaoke versions or cover versions. Do you get paid the same as you would for an Eddie Rabbitt track when people do those versions?

ES: No. No, that’s part of the deal when I say we’re trying to get it right. There’s so many inequities in it. It’s kind of complicated, actually. To be frank with you, there’s people that put out versions of your songs that are famous songs and they pay nothing. They just use it. So, there’s not much you can do about it. I once experimented – a few years ago I went online to see if I could get every one of my songs for free, it’s not right. It’s just the way we make a living. You can’t use any film for free. But I wanted to see if I could and you it was possible for you to get any song you want for free, actually. And record it.

MM: That’s astounding.

ES: It’s easy to listen to for sure, but they also record them, if they have the right gear. It’s not that complicated. Digital gear like a CD burner or a DAT machine or something.

MM: What do you think about the comeback that vinyl has been gradually making?

ES: I think it’s really wonderful. I really do. I was talking with a guy who owns one [record making plant] here in town that’s been around since long before I got to Nashville in the ’50s. And he told me that they are building a whole new building because they’ve got so much business making records. And some of it’s really fine vinyl like Japanese vinyl, too. My son, who is eighteen, he buys exclusively vinyl albums and plays them. He’s not even really interested in the other. He just thinks it’s cooler.

MM: I read the other day that cassette tapes are starting to make a comeback. I think that is pretty weird.

ES: That is strange because the quality of a cassette is not that good. It’s noisey, you know, compared to anything else like vinyl.

MM: What did you think when 8 track tapes came out?

ES: Well, I was glad because the first Eddie Rabbitt stuff was on 8 tracks. Before that, it was just reel to reel. Kind of an improvement, you know? I still have some of those but I don’t have anything to play them on.

MM: Yeah. Me, too. The thing I didn’t like about them was how sometimes it would switch tracks in the middle of a song.

ES: [Laughs] Yeah, it did. But, you know, it sounds like you’re a collector. I collect. I still have albums from the San Francisco days. And I cherish them. I love them. I have a turntable that’s a USB turntable and I work in Pro-tools a lot for recording and there’s a thing I bought called Audacity and it’s a two track Pro-tools. You play your USB turntable into it and it puts the two tracks – the stereo tracks – on a Pro-tools thing and it has this little software built in and you can take the clicks and pops out and everything. And then you can make a CD off of it.

MM: I have a USB turn table but I haven’t bothered to hook it up to the computer and install the software yet.

ES: Well, Audacity is what it’s called. It’s great. It’s not very expensive. And if you have records that are real noisey when you play them on vinyl and it’s too much you can get some of that out of it.

MM: Some of the songs you’ve written have been done in foreign languages. Did you ever translate any of those yourself or were they always translated in the countries where they were done?

ES: Yeah, they usually do it overseas. The publisher or the record label has it done. And it’s very funny, some of them. I had one called “Danger of the Sea” but it’s “Danger of a Stranger” and it goes, “ when you love her and she loves you but you don’t like to love the one that you’re tied to” and they said “you love her and she loves you, but you don’t have love on your tattoo.”

[Both laugh] Sometimes it comes out like that you know? I was asking a friend of mine that’s half Colombian that I was writing with, a guy named Phoenix Mendoza, he’s American but he sings in both Spanish and English and I asked him about writing in Spanish and he said, “It’s kind of limited because most of the words end with a or o sounds. So, you’re kind of limited to how you can rhyme things.” So, that affects the way they do the translations, too.

MM: I remember in the movie Roadhouse with Patrick Swayze his character played in a cage because people in the club would throw bottles at him. Did you ever have to play in a cage? Or were you ever at any of those shows?

ES: No, that’s usually something that happens down like in Texas. It’s like bars. Bar room stuff. And I never really played a lot of bars. I just didn’t. When I was in San Francisco, I played in folk clubs, where people aren’t drinking and getting nuts. So, I’ve never played to really Honky-Tonks. It’s usually the guys I know from Texas who went through that. Or down in the deep south. But it does exist, that’s for sure. It does happen.

MM: Even today?

ES: Oh, yeah. There’s places that have that going on. And there’s places that have chicken wire up.

MM: Wow, that’s incredible.

MM: What do you think of country music today. Has it gone too far in the pop direction?

ES: Well, I think there always has been some fantastic songs. Like recently, not too long ago, “The House That Built Me” [by Miranda Lambert] – a friend of mine wrote that song, actually – and songs like “The Song Remembers When” [by Trisha Yearwood] and “I Can’t Make You Love Me” [by Bonnie Raitt] and Keith Urban has some great songs. There’s always some great songs. No matter what’s going on in the mainstream. Right now, there’s a thing that’s going on and I think it’s because most of the artists are making their money not from sale of CDs anymore, they make their money on stage doing big shows. That’s their livelihood, mainly. Because their record sales are way down. So, I think they record songs that are very up-tempo and people chant to it and raise their fists and sing along. So, I think it’s effected what’s on the radio. And what’s popular. Because of that. So, it’s a natural thing. They’re just doing what they have to do, I think. But every once in a while something fantastic comes up on the radio that is not anything like that. It always shines, you know? There’s always somebody like Adele, somebody that just shines through, just totally real and different. And meaningful. So, I don’t really have anything against what’s going on. I just think that’s what is going on.

MM: I always thought a lot of the songs you did, like with Eddie Rabbitt were more like pop rock songs. I never thought of them as country when I would hear them on the radio when I was younger.

ES: Yeah, well, you know, my wife, she didn’t know Eddie Rabbitt as a country artist. She heard “Suspicions” and thought he was a pop act because it was a pop hit, too. And at that time there was a country crossover with pop. And people have asked me about this before and I go, we weren’t trying to do anything particularly style wise. We were just doing what we loved to do. And it was because I came from California and I liked Creedence Clearwater Revival and all kinds of music. And Eddie was actually from New Jersey and he loved, actually, hard country music. So, we had a thing that happened when we wrote together that was a combination of all those styles and I think that’s the way a lot of people are. You said you collect all kinds of music. Well, that’s what I did. I loved everything from Buddy Holly to Jimi Hendrix. So, you kind of do what you love and we weren’t really trying to be a pop act, though we had 15 pop records that were huge. But they were also number one country records. So, that was just a fluke in the way things were happening at that time with radio. That they accepted the country based songs on pop radio. I would say we were right at the forefront of what was going on with that, but I always tell everybody we weren’t trying to change anything. We were just doing what we loved. And hopefully somebody else would love it and that’s what our whole thing was.

MM: With Dr. Hook with “When You’re In Love with A Beautiful Woman” in particular, I always knew that song as disco.

ES: Well, it was really written like a slow – not slow, but like a groove like Smokey Robinson, and the producer of Dr. Hook put a beat to it that was reminiscent of disco. He wasn’t trying to make a disco record, and it wasn’t a big disco hit, it was a pop hit, but it got lumped in there because it came out during that time and it had that four four [beat] that drove it. Boom, boom, boom. And if you had that during that time you were disco. But I was there when they were recording it at Muscle Shoals and I didn’t really like what they were doing. But after I listened to it for a while I understood that they were trying to make a radio record and I accepted it. As it was going up the charts, I used to say, man, that guy’s a genius. The father it got up the charts, the more genius he became.

MM: He earned the name doctor.

ES: Yeah, he did. But that was a party band. My friend Shel Silverstein wrote almost all their hits. So, they were just trying to make something that would be played.

MM: At one point you met Tina Turner and she asked you to write her one of your hit songs but you somehow blew it. What happened there?

ES: My ego got control of my common sense. I was sitting with her and Dolly Parton at a table and that’s something right there. Those are two beautiful women. So, I was just kind of lost in the thought that I was sitting there with Dolly and Tina Turner. But Tina had not really had a hit for a long time at that point. She hadn’t done “What’s Love Got To Do With It” yet. She goes, “Why don’t you write me one of those hit songs?” My brain was going, nah, she never makes any records that are successful anymore. And what I should have said, as I said in my book, I should have said yes, what’s you’re address, what’s your phone number? Yes, I’ll do that, you know? I was an idiot. I really was. I was stupid for not doing that. It was just one of those rare times where I lost all common sense. Because she’s one of my favorites. She really is. My wife collects her autograph and stuff. I just love it. I’ve seen her play live two or three times. I think she’s fantastic.

MM: In your book you talk about a song called “Long Story Short.” Has Kenny Chesney released it yet?

ES: Not yet. Not yet. Actually, I went by his producer’s office yesterday and dropped off a couple songs to see because he’s getting ready to record. The last album, he didn’t tell me, but he told Paul, who wrote that with me, and Scotty Emery, he told Paul he was thinking of putting “Long Story Short” on the last album he did but he didn’t do it. He ended up not doing it. So, there’s not much we can do about it. Just hope for the best, you know? But we’ll keep pitching it because we really believe in that song.

MM: I’m curious to hear it after reading about it in your book.

ES: I do that song live and people just love it. People quite often ask me if when you write a song, if you know it’s a hit. I have had something like that. “Beautiful Woman,” I knew would be a hit. I had great faith in that song. “Crazy in Love,” I felt that way. “Drivin’ My Life Away,” I felt that right off the bat. I never lost faith that that would be a big hit. And “Long Story Short,” I have that feeling about.

Buy Even Stevens’ Someday I’m Gonna Rent This Town on Amazon.

Extra special thanks to Even Stevens for doing this interview. Thanks also to Brian Mayes at Nashville Publicity Group for making this interview happen — he’s a rock star, I tell you.

Leave a Reply