interview by Michael McCarthy

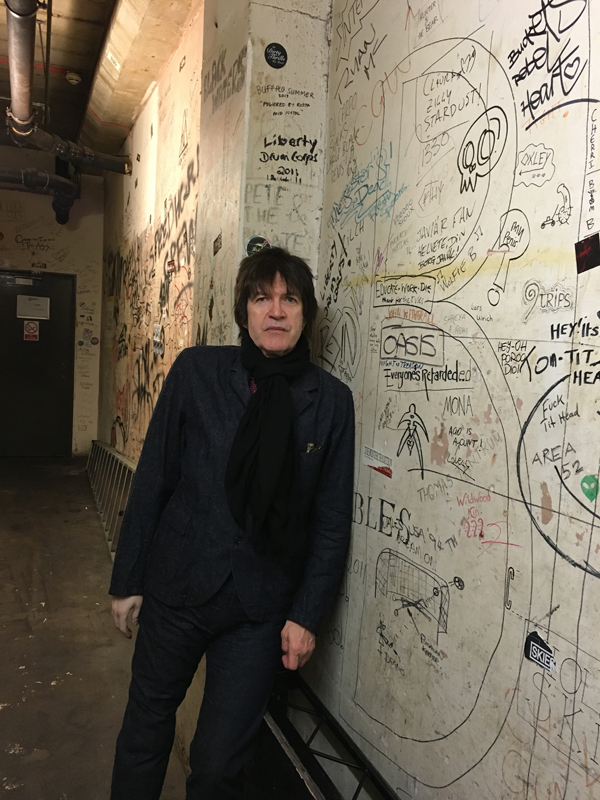

Today we have an interview with a brilliant lyricist and a true rock star, Edward Rogers, originally from Birmingham, UK, but who immigrated to the United States when he was 12. If you’ve never heard of him, that’s all the more reason to read this interview and get to know him. (He’s quite fascinating and a great talker.) Another way you could – and should – get to know him is by listening to his new album, TV Generation, on Spotify below.

Edward is like a living music encyclopedia and he takes that knowledge and colors his own music with it, crafting something that’s a bit like The Kinks, The Beatles, The Rolling Stones and The Who, all rolled up together. Big names, right? Well, if there was any justice in the world, Edward would be just as big as Ray Davies, Pete Townsend or Paul McCartney. He’s that damn good. His melodious songs always have an edge, but blended with beautiful harmonies, not to mention addictive hooks. TV Generation is easily one of the best albums I’ve heard all year and if you listen to it while you read this you’ll know why.

ER: Hey, Michael, how are you?

MM: Good. How are you?

ER: Oh, I was just finishing off a vocal for a track that I wasn’t satisfied with that I was working on yesterday. Sometimes I find that if I get up first thing in the morning and I hit it without any voice exercises it sometimes ends up being like, hey, I couldn’t have done that if I tried it 50 times.

MM: That’s true. I write novels, as well as doing the music site, and I definitely find that I do my best work in the morning.

ER: Well, the strange thing is, with me, I can struggle with and go through vocals 20 times. It’s all in the brain. Well, not really, it’s in the brain but you stumble through it then you look back and you’re like that’s really good. It’s the stumbling thoughts, I think.

MM: So, are you thinking about your next album already?

ER: Well, you know, I’ve got about 30 songs written that I’ve been working on. I believe in consistency in the work so I try to put aside two days a week to sit there and write songs. It can be “Mary Has A Little Lamb” and I write it 5,000 times. But it’s like, OK, the next “Mary Has A Little Lamb” might have another thing to it and click. Turn into something, you know? I also suffer from a little bit of the phobia of, I want the next song to be good. I believe in practice makes perfect. How do you get to Carnegie Hall? [Both laugh]

MM: I understand you were born in Birmingham, England and lived there for the first 12 years of your life.

ER: I did indeed, yes.

MM: So, what prompted the move to New York City?

ER: Well, I’ll tell you what happened. I came home from school one day and was called into the front room of my parents’ house. It was always a big occasion. I was like, I don’t think I’ve done anything wrong but, then again, I don’t think I did anything right. They told me, “We’re moving to America.” [Laughs] We’re immigrating. [Both laugh] And back then a lot of people were emigrating out of the UK. Either going to Australia or America. And my parents’ sister had moved to Australia so there was a big inclination to go to Australia. But we had some relatives living in America so they flipped a coin and America won.

MM: [Laughs]

ER: Thank God. In a major way. Because I don’t know what I’d be doing in Australia. But I do know what I’ve done here and I’m really happy to be here in America.

MM: Is it Brooklyn that you’re living in there in New York?

ER: I’m living in New York City. In the Joey Ramone building, actually.

MM: Oh, wow, that’s cool.

ER: Yeah.

MM: What are your favorite and least favorite things about the city?

ER: Favorite and least favorite. My favorite is [that] I can go out of this building at any particular point in time and find what I’m looking for within five or ten minutes. So, life goes on 24/7 when they talk about New York City. It’s great. Sometimes, on the other side, I go to friends’ houses and I’m away for a while and I see the other side of it, the lack of stress, the laid back environment. I kind of envy that, too. So, it has both sides. You’ve gotta live on one side of the fence or the other. I lucked out because I’m in a really good building in a nice apartment and I’m in the back of the building so there’s no noise. So, I’ve got a little bit of that. Still, there’s something to be said for going outside and having scenic views that are different from the 24-hour lifestyle that goes on here.

MM: It reminds me of when I lived in Glendale, California. I was in the downtown area and my apartment was in the back of the building so I didn’t hear any of the commotion. And the cool thing is that Glendale is in the valley so you’d get on the bus and two minutes later you’re seeing all the hills and everything. So, you have kind of the best of both worlds.

ER: Yeah, you had the escape factor right next to you, which is great.

MM: Yeah.

ER: Where are you living now, Michael?

MM: I’m in the Boston area of Massachusetts. Probably my accent shows something, right?

ER: Yeah. [Laughs] That’s why I asked, actually. [Both laugh]

MM: You have a bit of an accent. Do you think part of it is from Birmingham or do you think it’s just straight up New York now?

ER: Because I do radio and I also go back and forth to London – we just finished a tour of England about two weeks ago – I think when I’m around more formal situations, it’s probably a little bit more English. Most people kind of detect a little bit of an English accent. And it does come through with the way I communicate with people.

MM: I know your press release mentions your Brit Rock and Brit Pop influences. Who are some of the artists from England that you would cite as your biggest influences?

ER: There are so many at any given time. It changes all the time. When I’m thinking of lasting influences, obviously people like Ray Davies come to mind. Scott Walker comes to mind. There are those type of influences that are always there. I don’t try to write like them, obviously, but it’s in my blood. It’s always been there. I’m a huge fan of the Marriott/Lane writing combo. I’m also a Kevin Ayers fan. So, if you want to define it, it’s kind of like that Brit Folk, that Brit little bit of humor that goes in. I love Paul Weller’s influences. I’m also a Robert Wyatt fan. If you had to tell me, what am I? The first thing I would say is I’m a music fan. That’s where it starts. And I’m just lucky enough, after many years of trying, to kind of have my own musical situation. It’s kind of my dream come true. I love Roy Wood. I love John Fox. I could carry on for hours about these people. And I also love the producers that are great. Andrew Love. Lou Alder. All that work is marvelous to me. Mickey Most productions are great. And I’ll also turn around and tell you The Flaming Lips’ productions are great, too. The Nick Cave works are really great. I’ve got a wide spectrum of musical tastes and that’s one of the great things. Being a fan, I can take the influences of somebody new and the influences of somebody like Joe Meek, put them together with my own vibe, and create a piece of music that appeals to me.

MM: I know you started off playing drums. How old were you when you started playing those?

ER: Well, I was 22 and a friend of mine came into the house one day. He’d had this epiphany and he was having troubles domestically with his wife and he goes, “I’m gonna make you a drummer.” I was like, “What?” So, he took me out, we bought used drums, and the next thing I know I’m with this guy who’s learning guitar and a bass player who wants to be a football player and I’m with a guy that thinks he’s Keith Richards and can play really well. I’m thinking to myself, this is the most insane thing. But everybody – except for the bass player – had a walking encyclopedic knowledge of music. So, after a while this band Route 66 started to have a rock ‘n’ roll vibe and fairly soon in the game I realized that everybody was writing. I was like, OK, this is good. I should write. I should really write. So, I got a couple of my songs in there, too, and then it’s kind of like that song “Stardust” by David Essex. This time someone said to me, “You know, you should be writing your own things and you should be singing.” I got tired of lugging around the drums. I’m always the last one out of the club and I’m always the one that has to pack the drums in. And it became a little like, let me work on something that I can do.

MM: Before I ask you about your accident, I wanted to mention that I have PTSD from a car accident where my car went in the river with me in it. So, I don’t mean to be nosy, I just sort of relate to traumatic things.

ER: Ah… I can’t even – you know what, at least with me, it was done and I woke up three days later. I can’t imagine the terror of your car going into the river. Just what you experienced. God, that must be nightmares for life, you know?

MM: But what happened to you (in a New York City subway accident in 1985) is more life-altering.

How old were you when that happened?

ER: Well, I was 32 when that happened. If I could look back now at it, it’s just part of my everyday situation. I’ve bounced back. At the time it happened, it was done. It was over. There was no decision. There was no fore-thinking. It was like, I was on the subway and then the next thing I know I was waking up in a hospital and someone’s telling me, “You lost your arm and your leg.” And I was like, “But I still have glass in – ” and they’re like, “No, that’s what they call phantom pains. You don’t have anything there.” And I reached with my arm over to where it hurt and I realized there was nothing there. That was pretty much a shock. But on the other side of it, they say when you lose some part of your body or whatever, you gain something else. And I think [I gained] my constitution to do things. I had to work to learn how to walk again, and then function as a human being again, and get back to work and living again, [so] my constitution was challenged every time. It probably made me more strong-willed.

MM: Did you lose anyone in the accident? Or were you alone?

ER: I was just by myself. It just suddenly happened. Do you know what happened?

MM: No, just that it was a subway accident.

ER: I was in the subway and I felt faint and went to the door and the door opened and I fell off. And I guess somebody must have pulled the emergency. I fell out, the train rolled and I lost my right arm to my shoulder and my leg BK – below the knee. So, I’m on the subway and the next thing I see is I’m coming into this bright light thing and I’m looking and I’m seeing this dolphin and then it seemed like it was a green dolphin, and I see it swimming in front of me, and I feel like water on my cheeks and I feel like someone must be tapping me. What it was, there was a doctor leaning over and on his lapel, he had a green dolphin pin. That’s what I was seeing. When I came out of the coma.

MM: So, you were in a coma for those three days?

ER: Yes.

MM: Was it medically-induced or was it just the result of the accident?

ER: It was a result of the extent of the accident. They didn’t think I was gonna make it for two of those days. Again, the one wonderful part about it is I don’t remember it and I don’t really want to know about it because my situation was that it happened and I moved on.

MM: I was just thinking – Def Leppard’s drummer, Rick Allen, lost an arm and he continued playing with a specialized electronic drum kit and still does. Did you ever think about doing something like that or were you no longer interested in drumming?

ER: Well, you know, it’s funny you bring that up. I did go back to drumming with a couple of bands and had a couple of indie recordings out. It’s interesting again how you compensate for not being able to cover a full drummer’s menu type of thing. You compensate with your timing. My time got very Charlie Watts-like. It was very precise and there weren’t many fills, but the snare and the toms were very on time. It was simple. And then one day I was just told by a really well-known producer, if your band that you worked so hard to promote and push, and you’re the one that’s doing all the promotion for, if they get signed, the first person that wouldn’t benefit from this would be you. Because we wouldn’t use you. We’d use a session drummer. We would need those fills. I know your timing is great, but there’s a fullness we would need for the recording process. And I was thinking to myself, that’s someone telling me like it is. Everybody wants a certain extent of recognition for their work.

MM: Was it after that that you really took up songwriting full-time?

ER: Well, I’d always dip my toe in it, but I never really had gotten the whole down pat part. I was lucky enough that one night I was out and I ran into a singer/songwriter. I don’t know if you know George Usher, but George Usher is a fantastic songwriter. He probably has nine or 10 albums out under his own name and he was looking for a change in a writing partner. And we got together and we just found it really, really easy to write together and we shared the same mutual respect of artists and, also, different ways of writing. We wrote 55 songs together over the course of the seven years we worked together. So, that was a great learning experience. And at the time computers were coming out so then you had Garage Band and you had Logic and you could use sampling. It gave me this entire orchestration of sounds that for demo purposes I could write and then play for somebody and go, here’s what I’m looking for. Now let’s make it sound live. And that’s the magic. You know, it’s like I thrive on finding new sounds and going, “OK, here’s what I’m hearing on this.” So, when I give a song to somebody, for example, a producer I’m using and one of my best mates is Don Piper and I’ll go to him and go, “Here’s 40 songs – pick the ones that you think are good.” Or, “I think these ones are good, but besides these what do you think?” Through that, I’ve also gotten involved with writing with other people. That’s been a great experience because some people I never thought I’d work with I got to work with. And then you learn from them and your pallet gets a little bit larger. The real fun to it is going in with an idea of words and creating a piece of lyrically sound work. Or maybe it’s a skeleton and then you go in and you cut music to it and see what inspires you and how it all fits together like a jigsaw puzzle.

MM: I was wondering what you usually start with. If it’s programming beats or the lyrics or… how does the magic happen?

ER: That’s the wonderful part of it. There’s no consistency. I worked with John Ford from The Strawbs and Hudson and Ford and he sent me a couple pieces of music and I wrote the lyrics, sent them back. He sent me back what he thought was happening. We just made progress back and forth until we had the words and the music. That was one way. Normally, what I try to do is have maybe 10 sets of lyrics and then I’ll go in and just start playing with something and see if any of those 10 sets of lyrics connect in some way.

MM: Have you written songs for other artists?

ER: Yeah. Well, I’ve had other people cover my songs. John Ford is one example. Trying to think who else now. John is the first one and he’s a pretty hard guy to please. In Europe he’s had some huge successes so I’m really happy to work with him. I don’t know if you know a song by The Strawbs called “Part of the Union.” It was one of the biggest-selling singles. They had a big song called “Part of the Union” and he wrote that and it was one of the biggest-selling singles in the ’70’s in England. And I’ve worked with Marty Willson-Piper of The Church. And, like I said, seven years with George Usher for me was a virtual learning ground of opportunities.

MM: Do you write songs by yourself now? Or do you have new partners now?

ER: Nine-tenths of it are written by myself. As the game has moved on and time has gone on, I find the excitement of writing with different people. I’ve now developed writing partners that I use. Because I generate so many sets of lyrics, I’ll send them out to people and see what people come back with. And if it’s as good as something I’ve done or better I’ll use them. The opportunity to sit and write with somebody is always a great social. Sometimes nothing comes of it. And other times you can spit out three songs in a session. That’s the way it works. For this album two of the tracks are written with a gentleman by the name of Steve Butler. A great songwriter. He works with The Hooters and people like that. And we got together and we had a mutual affection for a singer/songwriter called Duncan Browne and we wanted to create that type of feel and we did it.

MM: Which two songs did you do with him?

ER: On this album, I co-wrote “20th Century Heroes” with him. And I wrote a song called “Terry’s World” and that was the song that was in the Duncan Browne feel. “20th Century Heroes,” we went down and recorded it down in Philly with some of his mates from The Hooters and I just didn’t like the feel. So, I came back and cut it with my own band and we’ve got a little bit more of a New York grit feel to it.

MM: TV Generation was produced by Don Piper. How did you connect with him? And what was the process of working with him like?

ER: I’ll tell you what happened. I went to a party one night and there was this band playing, a band called the Don Piper Situation. I heard him play and I heard him sing and I went, damn, I would like to work with him. And I was working with George Usher at the time and he and I were producing our own records. I said we’ve gotta use this guy Don Piper. And a tribute album came up – I think it was a Buffalo Springfield tribute – and I said let’s try Don Piper out. And we cut a track with Don and it just became instant that Don was the perfect person for me. Because he didn’t have a sophisticated studio in the early days, some of the processes to record were harder. But it was good because it was a learning curve. We did this track together and I said, “I would like to do an album with you.” We did an album, and it did well, and we got signed to Zip Records and they put it out. They were very enthusiastic about it and we’ve been working together since. And Don’s a really good mate. Everybody has a style and he just has a style where I trust his intuition. Nine tenths of the time he’s telling you not what you want to hear but what you need to hear. Then you have a choice to make your own decision. But he’ll tell you the facts. You need people around you to tell you the truth. I hate yes people. I’ve worked with a lot of yes people. The people who tell you in a heartfelt way, and not a self-motivating way, are the people you want to work with. And every record we up the game for him and for me. This record’s done, the next one is gonna be upping the goal again. That’s one of the things that I thrive for. Each record has a purpose. Before each record goes to anybody, I have to feel it’s one step ahead. For fulfilling my ambitions.

MM: What was the first album you did with him?

ER: You know what, I had a band called Bedsit Poets. It was one of my new directions at the time. It was a young lady and myself, Amanda Thorpe, and also a rock writer by the name of Mac Randall from Boston, actually. And the three of us had this little project. It was kind of English folk with a little bit of pop thrown in there. And we got signed to Bongo Beats and they gave us an advance and they were based in Canada and we got a lot of exposure because we were signed to this Canadian label. They thought we were Canadians. They couldn’t tell our English accents. [Both laugh] She really has an English accent, which makes my accent come out even more. So, we were getting a lot of airplay over there and the label gave us money for second album and I said let’s try Don Piper. So, that was the first full album that we did with Don. We had a really great time with him. Amanda moved back to England, so that broke up the Bedsit Poets. I decided then to really concentrate on my own stuff. I’d already been working with George Usher. We had twin careers going on.

MM: Since one of your songs is called “20th Century Heroes,” it made me wonder who your heroes were when you were a kid?

ER: When I was a kid? Wow. [Laughs] Slade. T Rex. The Beatles. Bowie. You know, Slade, to me, were such an institution because I just thought they were so much fun. Yet they were a lot better writers than they get credit for. Lennon/McCartney were obviously such icons.

MM: I love the way your songs like “Terry’s World” and “Alfred Bell” tell stories, which made me think of The Beatles. Do you prefer writing songs that tell stories? Are those more difficult to write?

ER: It’s what strikes you. I know you’re a writer and what we were talking about earlier is that it’s what strikes you. Part of the reason I wrote “TV Generation” is because we all watch television and as we’re watching television sometimes something will pounce out. There’s a song on the album called “On An Ordinary Wednesday in June” and that came from watching the television. Dylan Roof went into that church down south and killed nine black people. I’m watching it live as the news came on at noon and I went in the other room and wrote down the story and the story was finished. That was just one. When stories come up, I love when I can tell them the way I feel like they ought to be told. “Terry’s World,” I live right on 9th Street, and a block and a half from here for about 50 years was this little wooden shack in the middle of 9th Street where a guy had a news agent shop selling newspapers and candy and magazines. He was there day and night. In the cold and in the heat. This little man was in there and it was like, what was his life like? Did he have a home life? He was there at six o’clock in the morning. He was there at eight o’clock a night. He was there six days out of seven, so obviously he had one day off, but was that living life, you know?

MM: You have some terrific horns on the album. Are they actual horns or are they synthesized?

ER: That’s a mate of mine, Geoff Blythe. The interesting thing is, and we didn’t know this for 30 years, but Jeff grew up on the same road I did in Birmingham. When I emigrated he stayed and he was one of the founding members of the Dexys Midnight Runners. He later went on to work with Elvis Costello for 10 years and Black 47 for 30, 35 years. If you look up Geoff Blythe you’ll see he has an extensive catalog of work. We brought him in to cut one or two tracks. And while I was there I was like, “Let’s just put him on a lot of tracks. He sounds freakin’ awesome.” And Geoff was just like, “Give me more, give me more.” He’s an amazing player and a really good mate, which is even better.

MM: I really love “You and I,” which has to be one of the sweetest ballads I’ve ever heard. Who plays the mellotron on that?

ER: That was Joe McGinty, who started out being a member of the Psychedelic Furs. Now in New York he’s mainly known for Loser’s Lounge. He’s the founder. An extremely talented piano player of any type. “You and I” – again, you being a writer – it took me forever to come up with a set of lyrics that made sense to me. I kept second guessing myself. When it was done, the music and the song, I just looked at it and went, wow, I really did it. But I really sweated it. And normally the ones you think are the best are the ones that come the easiest, but that’s not always the case.

MM: Do I detect some female background harmonies on “Gossips Truth and Lies”?

ER: Yeah. There are some female vocals on there and that is a lady by the name of Caitlin O’Riordan, who was the original bass player in The Pogues and she was also, I think, married to Elvis Costello for 20 years. She’s got this tender set of vocals, which is not her personality. After playing with The Pogues, you can imagine. “I’ll hit you with the bass,” type of thing. She came in and she was soft spoken and she started singing and we went, wow, let’s put her on a couple of tracks and see where we end up. If you look her up on Facebook you’ll kind of get an idea of what she’s like. Think of the work she did on this record and you’ll be like, oh, that’s contrary.

MM: You mentioned doing a tour in the UK. Do you have any other plans to tour right now?

ER: We’re doing a record release on the 20th at The Cutting Room, which is in New York City. After that we’re looking at some options. Looking to see what our booking agent gets us. Like I said, we just finished the tour. So, right now, it’s let’s get the record out, do the press and do the promotion we’re supposed to do then do the record release and pick it up from there.

MM: How did the UK tour go?

ER: Great. But I’ll tell you, everyone who thinks rock ‘n’ roll is a really great job, I think sometimes they don’t know the hard work that goes into it. We went over there and we were there for two weeks and we basically played one to two shows a day during the course of the tour. We had a couple of days off. But when you’re traveling you get up at six in the morning, you travel until two in the afternoon, you do soundcheck, you have something to eat, you may have two hours. Now in two hours, you can either go sightsee or take a nap. Then you do your vocal exercises and then you get ready, and you go on and do your show for maybe 45 minutes or an hour, and you come off and you’ve gotta meet and greet people. Now it’s two o’clock in the morning then it repeats itself. That’s what it was like. Luckily enough, we had two days off. One day we rested. One day we went out and did as much of London as we possibly could. But then we end up tired again because we partied too much on the second day off. It was great. We met a lot of people. Saw a lot of countryside. Saw things from a distance. It’s like, “There’s Stonehenge,” as we go whizzing by.

RANDOM QUESTIONS:

MM: What was the first album you ever bought with your own money?

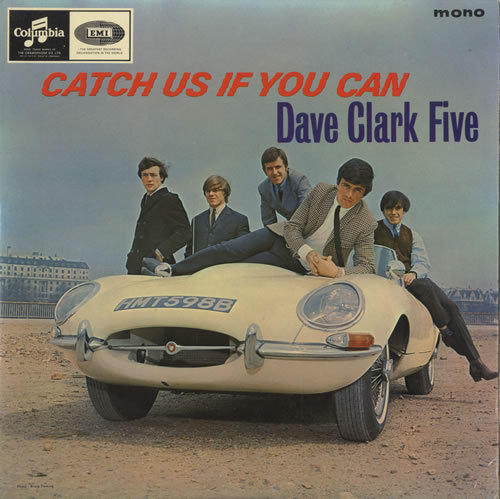

ER: Dave Clark Five, Catch Us if You Can.

MM: Cool. That’s one question that it seems like everybody remembers. Like losing your virginity. It always stays with you.

ER: Let me tell you the first single I bought, which was “Not Fade Away,” the Rolling Stones.

MM: What are three things off of your bucket list that you have yet to do?

ER: Any bucket list that I want to pick? That’s a good question. OK, get to a point that I’m comfortable as an artist. That I feel I’ve achieved a certain level of success that I’m satisfied with. And that doesn’t really have to do with [the] size of record sales. It’s getting to feel justified for what I have done. Second? Opening for a couple of artists that I admire like Paul Weller or Ray Davies. I’ve been lucky that I’ve opened for Dave Davies. That was one of my biggest thrills. And I’ve opened for Ian Hunter.

MM: That’s really cool.

ER: Ian’s a great guy. That’s one of the great things about the work I’ve done, everybody you get to meet. And the third thing would be to visit Amsterdam, preferably to play there on one of our tours. I’d love to just get down to Amsterdam because that’s one city that everybody loves and I’d love to see that. I don’t want the world. I never want the world. I don’t want to be mega-successful. I just want to move into the next level.

MM: What’s your biggest pet peeve?

ER: OK, my biggest pet peeve is when people are late. I’m notorious for trying to be on time. I can’t say I do it 100 percent, no one can, but I hate when people are late for appointments.

MM: I don’t like it either.

ER: I’m there and I’m waiting – and it’s not two minutes or five minutes – it’s when people don’t value your time enough and they keep you waiting for hours.

MM: Who are three artists from your parents’ record collection who you actually liked?

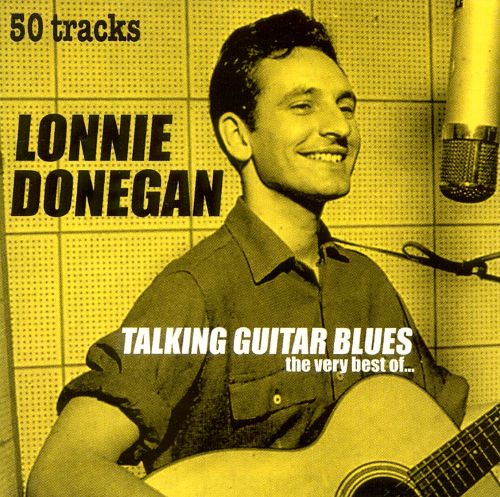

ER: [Laughs] All right. Well, my parents’ record collection was quite limited. [Laughs] But I’ll give you Lonnie Donegan, Ken Dodd, and I think my mom had a thing for Little Richard, so I’ll give you Little Richard.

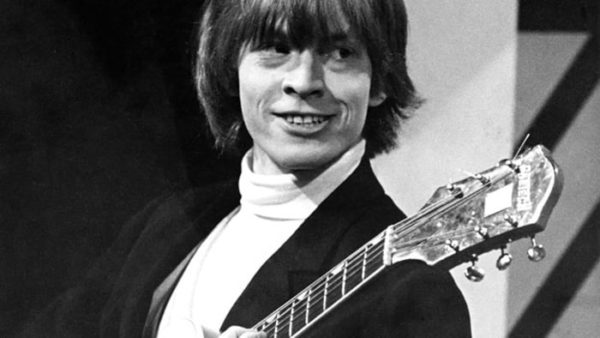

MM: If you could resurrect any one musician from the dead, who would it be?

ER: No-one from The Grateful Dead. [Both laugh] Wow, you know, I’ll tell you something, the most major musician that we lost, and was devastating to me, would be Brian Jones. I would’ve loved to see what he would’ve done. When I was a kid rock musicians didn’t die. You had one hit single and you were rich for life. And Brian Jones, to me, was such a major part of the Rolling Stones. Keith didn’t have anything on Brian Jones. But after you learn all the truths and the realisms, or maybe all the fabricated lies, but if there is one I would bring back it’s him. And there’s another one I’d bring back just for what he contributed to my life, and was taken in such a horrible way, is relatively a new person, David Bowie. It’s such an obvious answer because the man was so classy and his work will live forever. There’s a third person, of course. John Lennon.

MM: One last question. If someone was giving you a million dollars to give to charity and it all had to go to the same cause or charity, which would you give it to.

ER: [Laughs] That’s a really good one. Well, right this week Manchester is suffering with their pain. So, right this week I would give it to the Manchester Campaign. I used to work for a not for profit real estate company and I see what good the right charities can do. I’ve also seen how much money can be squandered. The real key to that would be to really research and make the right choice. But right now, because it’s on my brain, Manchester would be where the money should go.

Connect with Edward:

Leave a Reply