Interview by Michael McCarthy

Photos of Sarah by Phil Nicholls (www.philnicholls.co.uk)

Sarah McQuaid is fast becoming a legendary folk artist in England, although her career began in Ireland. She released her first album, When Two Lovers Meet, in 1997 and has been going strong ever since. Her new album, If We Dig Any Deeper it Could Get Dangerous, is her fifth solo release and sixth album overall, as she’s also released an album under the name Mama in conjunction with her former pop star friend Zoë. I have not had the pleasure of fully digesting her previous releases yet, but I should think that If We Dig… is her darkest album with several songs that reference death in different ways, as you’ll read about in the in-depth interview below. If only for that reason alone, I have a feeling that If We Dig… will wind up being my favorite of her albums. However, she’s also widened her sonic palette with this release, which contains ten original songs and two covers, whereas her first few albums only had one to three originals. She also plays electric guitar on the new album, which she does in an entrancing way that will have you remembering the guitar work just as much as her vocals and potent lyrics. If you’re looking for something a bit deeper than your average folk record and packed with metaphors that allow you to adapt the artists’ songs to fit your own life, then look no further. I’m not even a folk music junkie and I absolutely love If We Dig… and chances are you will, too. Read on and learn all about it and so much more. You can also give the album a listen while reading the interview, which I highly suggest you do.

MM: You were born in Madrid to a Spanish father and an American mother, but you were raised in Chicago. What prompted the move from Spain to Chicago?

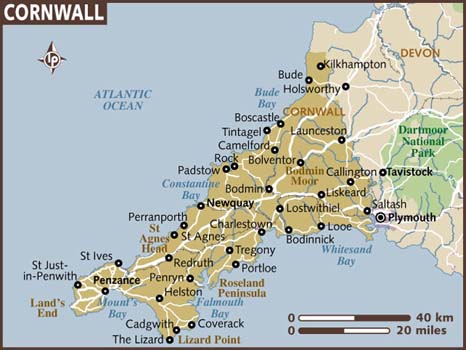

SM: I was born in Spain, which is where my father was from. I grew up in America in Chicago, which is where my mother was from. I moved back to Chicago, which is where she’d grown up and where all of her family were from when I was just one year old. So, I really don’t remember much about Spain, but we lived in Chicago until I was 13 and then we moved to Washington, D.C. That’s where I went to high school. Then I went to college just outside Philadelphia and wound up staying on in Philadelphia for a few years after I graduated, working in a wonderful music shop called Vintage Instruments, which sold beautiful Gibson and Martin guitars. I got to spend my days doing a lot of playing guitars and packing them up to ship them out to people and stuff like that. I say this because I was unpacking a guitar just this morning – because I just flew over the other day – and I was thinking back to when I used to pack guitars for shipment every day. But, yeah, I lived in Philadelphia and then moved to Ireland, which is where my husband is from. Lived in Ireland for 13 years with my husband and our two kids then moved to Cornwall in England just over 11 years ago. I live in a place quite near a town called Penzance, which is right on the tip of Cornwall, which is kind of like this long foot that sticks out into the Atlantic Ocean down on the lower left-hand corner of England.

MM: I understand Prince Charles owns a lot of Cornwall?

SM: Yes. The Duchy. Cornwall is a county, but it’s also a Duchy. It’s a Dukedom. Prince Charles is the Duke of Cornwall. And actually owns an awful lot of the property throughout the county. We have this interesting phenomenon in England where you can own a house, but you don’t actually own the ground that it sits on.

MM: That’s different.

SM: They have this thing called ground rent, which a lot of the time isn’t very much. A lot of the time the amount that was fixed for the ground rent was fixed back in like the 13th century or that sort of thing. [Laughs] It’s a tiny amount of money, but you’re still having to pay this tiny amount of money every year because that was established way back. It’s an interesting part of the world. A beautiful part of the world. Really gorgeous. A lot of beaches and cliffs and stuff.

MM: Here in the U.S. we have property taxes. They assign your house a value and base it on that.

SM: Oh, yeah, we have that, too. It’s called Council Tax. You have to pay taxes. So even if you don’t own the land that your house sits on, you still have to pay a property tax based on the value of your house.

MM: When you first moved to England from Ireland did you have trouble getting gigs?

SM: No. It was kind of great. I had just quit my job and become a full-time musician a few months before we moved to England. In some ways, the process of moving to England made my job a little easier because my mother, sadly, had died so we moved into what had been her house, which we weren’t going to lose even if I didn’t make any money as a musician. So, it made that transition a little bit easier. I was very lucky. One thing that is great that had happened was that right at that time – within a month between quitting my job and becoming a full-time musician – I was lucky enough to get a spot on an Irish TV program. It’s a program that’s called The View, but it’s not anything connected to the American The View. It’s an arts kind of chat show, really. They have different guests. And always at the last five minutes of the program, there’s a musical guest who comes on and does one song. And I got that slot, incredibly. I still don’t know how I got that. [Laughs] It was an amazing break to get. And also, I was lucky enough to get a video of my slot on Irish TV, which is still up on my website. You can go to my website, and it’s on Youtube and everything, and see my little TV appearance. But when I was writing to venues and festivals in England and saying, well, “Here I am, I’m moving to England. Will you give me a gig? And, by the way, I’ve played live on Irish national television. Here’s the Youtube of my live performance.” Well, they gave me gigs, you know? I thought that was such a great get.

MM: You play some beautiful guitar on your albums. Did you ever take lessons or are you self-taught?

SM: I never took lessons on guitar. It’s funny, I was talking about this just last night with my cousin. I stayed with my cousin in upstate New York because he stores all my gear that I have to keep here in the U.S.A. Sound equipment and CDs and things like that. So, he’s always my first stop and he’s a musician as well. He gives lessons in guitar and piano and drums. He was saying he had no problem giving lessons in piano and drums because he took lessons in those instruments, but, like me, he’s a self-taught guitarist – he’s a good guitarist – but he said he struggles to teach people because he’s self-taught. And I had this, too. I tried giving guitar lessons and found out that I really wasn’t a very good teacher. Because I would just say, “Well, I don’t know. Just go figure it out.” [Laughs]

MM: Wow. [Laughs]

SM: I didn’t know how to help them. I was a terrible teacher. There you go. But, yeah, I’m self-taught. I guess my mother and my uncle played guitar and they both showed me some stuff and then I just kind of ran with it.

MM: We you exposed to a lot of folk music when you were growing up?

SM: Yeah, tons. Because my mother played guitar and piano – like myself, as well – and sang and her thing was folk music. She was really into Joan Baez and Pete Seeger and she had all these LPs by all these obscure Appalachian folk singers because she spent a lot of time as a teenager living in Kentucky and West Virginia, working at American Friends Service Committee work camps [see: https://www.afsc.org/content/archive-highlights-us-and-international-work-camps] helping people in impoverished Appalachian regions. She discovered a lot of folk music through that and became enthralled with it and had a huge repertoire of songs. She used to sit a lot of the time and play her guitar. She’d put me to bed and then she’d sit and play her guitar in her room next to mine and I could hear her. That was what sent me to sleep every evening. It was a lovely, early introduction to music. And my uncle played a lot of folk music, but my uncle also writes musicals. He’s still writing musicals and they win awards sometimes and get produced occasionally, and so he comes from a musical theater sort of emphasis and then I have another cousin who’s a classical musician. He’s the musical education director for the Dallas Symphony Orchestra, so he’s got that classical thing. And I’ve learned from all of them. My own background, musically, through my family. My family is super eclectic, but they all instilled a love of a lot of different forms of music in me.

MM: Spiral Earth described you and Zoë as “Two pagan goddesses channeling the ghost of Jim Morrison.” Did that help you get gigs, too?

SM: Yeah, that was another piece of super luck for me. Again, right after I moved from Ireland to England. I met this woman because our kids were going to the same little school. You have to picture this – in the entire school, which was a primary school for kids aged four to eleven, there were like 25 kids in the whole school. And my kids started going there, so they were really glad to have us. So, you just had two mixed-aged classes and all the parents got to know you because it was so small. And I got to be friends with this woman, Zoë, and found out she was an incredibly famous, former pop star who had a massive hit single in England. It was a hit to an extent in America as well, but in England, it was in the top five of the charts for sixteen weeks.

MM: What was it called?

SM: It was called “Sunshine On A Rainy Day.” It was kind of a dance single. It was in 1991. It still is to a large extent the kind of get everybody out on the dancefloor number that they play at the end of the night at parties and weddings. As soon as people hear the opening bars of the song they all go “Yay!” They all go out and start pumping their hands in the air. So, Zoë and me started writing songs together and wound up making an album as a duo of songs that the two of us had co-written. She taught me a lot about songwriting. Before meeting her, I was really more of a folk musician. I was writing songs, but I wasn’t writing many. I was waiting for inspiration. I had one of my own songs on the first album and two of my own songs on the second album. And in between making the second album and the third album, I met Zoë and we made this album together under the band name Mama. After that my albums started featuring a lot more original material. So, she really is responsible for changing my musical direction. To collaborate with somebody who comes from a completely different musical background. Again, it was a pop music, chart single type background, which teaches you so much about songwriting and I was so grateful to her, really. I don’t know if I would be where I am now if it wasn’t for Zoë.

https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLvKo07T2wcubNPbZSklhBEuPnWahl2noU

MM: Why did you call it Mama?

SM: Because we’re both mamas and we met through being mamas of little kids, you know? Our kids were kind of the same ages. Well, one of her sons was a year younger than my son and another was a little older. She had two sons and I had two daughters and they were all going to the same school when we moved to England. She was my first best-friend in England. And we thought, let’s call it Mama because that’s how we met.

MM: That’s cool. I would’ve been afraid that there were already several artists throughout the world using that name already.

SM: You know what? I was afraid. And thank goodness for the internet because I was able to go online and, amazingly, there was not a band called Mama. There was a South American alternative musician doing some music under the band name Mama but I didn’t think we were gonna get confused with him. It did cause a little bit of confusion initially on Spotify. I had to get onto Spotify and say, this is our album, that other one isn’t ours, it’s somebody else. But they split it up pretty quickly. We managed to resolve the confusion and get it all straightened out.

MM: I know you said Zoë taught you a lot about songwriting, but do you think it also took you until then to find your voice as an artist?

SM: Well, yeah, as I said, that was down to Zoë. What happened with Zoë is that we had this process of writing where we went OK, let’s write an album, let’s write some songs. And up until then, I thought I couldn’t just sit down and write a song. I had to wait for a song to strike me. It started out with one or two songs a year and then through Zoë, I realized I realized that I could write a song about anything. I didn’t have to wait for a song to come to me. I could go looking for the song. And once I realized that it was kind of an epiphany, really, and she also taught me that songs didn’t have to have three verses, a middle eight and a chorus. There has to be a structure, but the structure can be anything you want. So long as there’s some kind of discernible pattern that people can hang it on. That it could be anything. It was really liberating, working with her. And I started getting a lot more ideas for songs through working with Zoë, so while we were making the Mama album I had already started recording my third album, The Plum Tree And The Rose. I wound up actually writing new songs and I went, OK, I want to put these on the album so I wound up discarding a lot of material that I recorded and the album changed direction mid-flow.

MM: You’d found your voice.

SM: So that was a crossover album for me because I started writing it while I was still focusing on traditional music. I don’t like to use the word covers, [but] I always have at least one on every album. I think it’s a good thing to try and get your head in songs that other people have written. So, on the second album, I had a cover of a song by Bobbie Gentry and on the third one, I had a cover of a John Martyn song. The fourth one, Walking Into White, had a cover of “The First Time Ever I Saw Your Face” by Ewan MacColl. And on the new album, If You Dig Any Deeper It Could Get Dangerous, which came out in February, that’s almost all my own material, but I’ve got a cover of a great song called “Forever Autumn” by Jeff Wayne that he wrote with Gary Osborne and Paul Vigrass.

MM: So, you’ll always continue to do a cover or two on your albums then?

SM: I’ll always do occasional covers, but my focus musically at the moment is really on writing my own songs.

MM: The album cover art of your first four albums, in particular, look like they could be covers of children’s books, reminding me of The Little Prince and maybe some Disney. Are you the artist?

SM: I’m the cover artist of the artwork on the cover of my new album, which is a little bit more sketchy, but the artwork for the first four albums was done by a great friend of mine called Mary Guinan. She’s my son’s godmother and she’s a really close friend. We’re still close friends even though she’s in Ireland and I’m in England now. We communicate a lot. And she still does all of my graphic design, but when it came to doing the new album I’d sent her the album and said, “What do you think about a cover?” And she was saying, “You know, gosh, I don’t know. I can’t think.” And she wasn’t kind of feeling inspired and then I was sketching and I just wound up doing a little doodle – I wasn’t thinking album cover, I was just doodling – and I did this doodle of a spade that was leaning against our porch then I ended up drawing a little guitar. The whole thing about the title track of the album is “If We Dig Any Deeper It Could Get Dangerous” and it starts out “there’s a boy in a garden with a shovel and a spade.”

MM: And that was inspired by your own son, right?

SM: Yeah. He was out in the garden digging this massive hole for days. It’s still out there. It’s huge. And I went out to see what was going on and the hole was deeper than I thought and I said, “If you dig any deeper it could get dangerous” and I just heard the words come out of my mouth and the words really resonated with me. I thought, God, that could be a song. And immediately all these different levels of metaphorical meanings came to me. When I said it, I just meant it literally. But “dig any deeper” could be about all kinds of things. It could be talking about relationships and there’s kind of an allusion to fracking in the song that some people have picked up on. So, it could mean a lot of things. I like that when words can mean more than one thing. You can allude to all these different shades of meanings without being too heavy-handed because the main thing you want when you’re writing songs is for people to put their own interpretations on what you’ve written. I don’t want people to listen to the songs and think exactly what I was thinking. I want them to think my song relates to what they’re thinking already.

MM: Makes sense, although I do have a few questions about specific songs. My favorite track on the album is “Slow Decay.” You sing, “it’s a slow decay / like a note you hold ’til it fades away” and you sing about the body failing and what you’ll leave behind. So, I do have to ask if it’s a song about death?

SM: It is. Well, that song actually started just with the word “decay” because when you’re recording music you talk about decay and decay is the way a note gets quieter and quieter and quieter. And the note just keeps getting quieter and quieter. The note doesn’t ever actually really finish. It just gets to a point where people can’t hear it. And it’s the same kind of thing with sound-waves and waves in water. The way it continues. When you spend a lot of time surrounded by ocean on three sides as I do – it’s a peninsula, as I said – so you’ve got the beach in three directions and then the other way is land. So, you look at the water a lot and look at the waves. And they just go out and out and out or in and in and in. And then you think about sound and when you’re recording you’re looking at the wave forms on the computer screen where everything you’re recording becomes visual. I wonder if people had these thoughts when they were recording to tape and didn’t have the visual picture of the sound. I can’t think of sound without thinking of that visual picture. So, I was thinking about that sense of decay. And I was thinking I can relate that decay in terms of death. It’s leaving a bit behind and getting quieter and quieter to the point that you can’t hear it but that doesn’t mean it’s not there. And that made me think of death in a better way. So, I wanted to share that.

MM: I understand the song “Forever Autumn,” was originally written for a Lego ad. How did it go from being that to being such a haunting song on your album?

SM: What gave me the idea to do the song is [that] I was on tour and my manager said, “Hey, you know what’s on? We’re very near Manchester. And Jeff Wayne’s War of the Worlds is on.” I forget where it was, some big stadium. ‘Why don’t we go see it?’ We had a Tuesday night where there was no concert so we got tickets to the show and it was amazing. I knew the soundtrack of the show before because it was pretty well known in England. I don’t know if it was over here [in the United States]. The show started off as a concept album and that song, “Forever Autumn,” like you said, started off as a Lego ad. So, when Jeff Wayne started writing this concept album based on the book by H.G. Wells he took this Lego commercial that he’d written with these two guys, Gary Osborne and Paul Vigrass, [and] re-did the commercial so it was a full-length song. So, what happened was we went to this stage show and I came back and I was humming the song and Martin said, “You know, why don’t you try playing ‘Forever Autumn’ on guitar. I think it would sound really nice.” So, I got my guitar out and tried it [and] I went, “Yeah, actually, it’s really nice.” It’s quite a big song, the original version with Justin Hayward singing and it’s kind of nice to strip it back to the guitar. Or, in the case of the album, it’s a duet for guitar and cello. I had this fantastic cellist who was 16 or 17 when we were recording the album the year before that. So, yeah, I started doing that song live in my shows and people were always saying, “I love that Moody Blues song,” and I would have to say it’s not a Moody Blues song, it’s a Jeff Wayne song. The thing about “Forever Autumn” is it’s got that whole “you’re not here” thing and it’s kind of about death and decay and what people leave behind so it fitted with the theme of a lot of my original songs on the album. It just seemed to belong there. And, like I said, I always like to have one or two covers on every album and I thought why not have “Forever Autumn” be the cover on the new one.? It seems to fit really well, I think.

MM: I agree. Definitely. Now, you also have a piece called “Dies Irae” [mispronounces it like Diss Array].

SM: “Dies Irae,” yes. That’s the only other song on the album that I didn’t write. It’s a medieval chant. It’s all about the apocalypse so, again, it seemed to fit in thematically. It fitted in with the album for two reasons. One is that the opening few lines of “Forever Autumn” – the little instrumental intro, which is also on the original Jeff Wayne version – starts out with this “do, do, do, do, do, do, da, da, da, da, da, da,” which is familiar sounding because it’s been used as the theme to The Exorcist and a whole lot of other films. There’s a thing on Wikipedia about all of the different movie themes that have used that little sequence that comes from the “Dies Irae.”

MM: I was wondering how you took something that is usually rather chilling and turned it into something that is more so beautiful.

SM: Thank you. Yeah, it’s that spooky music. The thing about the “Dies Irae” is it has that link to “Forever Autumn,” but also in the title track, I use all this kind of apocalyptic imagery about the trumpet, and the fire and the flood, and the pale horse, and the trembling ground, and all that. All that’s in the Latin version of the “Dies Irae,” if you read the Latin version’s translation, all of that language about the apocalypse is in that song. It’s a beautiful and haunting melody and it gave me a chance to do a fun thing that I like to do sometimes where I play a harmony on guitar to the melody that I’m singing, so rather than the guitar just accompanying the voice, it’s like it’s a duet for the guitar and the voice. The guitar is as important as the voice. And because each melodic section repeats twice I do two different harmonies. So, I do one harmony line on the guitar then I do the higher harmony line with the next bit. So, the guitar is doing something different on every line of the song. which makes it interesting and challenging to play and then, of course, it was produced [by] Michael Chapman, who was a hero of mine for ages, and then I met him and he offered to produce my new album, which is just amazing. Another incredible piece of luck. I think I must have done something really good in a previous existence. A lot of good things have happened to me in this one. And Michael has also been another real catalyst in my life because he got me playing electric guitar, which is not something I’d ever done before, making an album, and on the track “Dies Irae” he’s doing interesting noises on his electric guitar and you hear all these kind of strange things. It almost starts off sounding like it might be a mosquito but not in an annoying way. He’s doing all that with a slide and the strings, making them jangle a little bit.

MM: “Cot Valley” has an interesting story, being about children who were forced to work in mines. Are there any stories about the children haunting the area?

SM: Oh, I’m not aware of any, but no doubt there are plenty of ghosts in Cornwall. But, again, that sort of brings us to the left behind thing. But there’s this beautiful place right near where I live called Cot Valley and I go there a lot because it’s not far from where my kids go to school and it’s a great place to bring the dog for a walk. It’s this beautiful coastal area. But one or two hundred years ago it wasn’t at all because there’s an old mine there – it’s still down there, but it’s not worked anymore – and as of the 1840s, 20 percent of the workforce in Cornwall were children. And it’s crazy. In 1842 the English parliament passed the Mines and Collieries Act and it said, and this was this really progressive law for the benefit of children, and that law said that from then on it said you couldn’t send a child to work underground if the child was under 10. The child had to be at least 10 years old to work down in the mines. [Both laugh] And all the mining companies said you’re gonna put us out of business. [Both laugh] We need those children under 10 down in the mines. How are we gonna make a profit if we can’t have children work who are under 10? And the thing was, they could still employ children above ground and the job they mostly gave to children under 10 to do above ground was running these furnaces, which extracted the arsenic from the tin ore because arsenic is a by-product of tin mining and it was a valuable byproduct so the kids got the job. The furnaces would burn down the tin ore and then the arsenic would be kind of a dust adhering to the sides of the furnace and the kids had the job of collecting that dust and scraping it off the sides of the furnace and bagging it up. That was an OK job for kids under 10 and then when they were 10 they could be sent down. A lot of people say they have this romantic image of life in the olden, golden days – they think, oh, wouldn’t it have been nice to live back then – but it wasn’t this lovely time. Life was a lot shorter for everybody and harder and we’re really lucky. You might [not] think that when you read the news and there are bad things happening all over the world but actually the world even with everything that’s happening [is better]. I’m happy that my kids are growing up in the world now and not in the world 100 years ago.

MM: I appreciate the sentiment of “Break Me Down” because I don’t like the idea of being cremated or buried in a coffin either. But if you had to write a will today, which would you choose?

SM: Oh, I would choose to have done exactly what I talk about in the song and luckily there’s a place not far from where I live where you can be buried in a wicker coffin so your body just decomposes naturally and becomes part of the soil, which is pretty much the most ecologically friendly thing you could do. A conventional burial in like a sealed coffin isn’t very good because it’s not very friendly to the environment and cremation isn’t good either because it releases all sorts of noxious gases. Being buried in a natural coffin that’s going to decompose – and there’s that word decay again – and literally break down into pieces and you become compost and then you become flowers and trees and I like that idea. I believe they have pioneered composting bodies. I read about a pilot program somewhere around Seattle where you can actually be arranged to be composted after you die. So, it’s a slightly quicker process than just the natural burial thing that I’m talking about and that’s good, too, there isn’t necessarily enough land for everybody to be buried in that way but compost speeds up the process and you can put it down directly to become flowers and fruit and vegetables.

MM: Very cool. On a different note do you feel more accomplished when you finish writing an original song or when you finish rearranging a classic?

SM: Um, I think totally equally. I think there’s at least as much creativity that goes into trying to put together an original arrangement of something that you haven’t written. I have this vague idea that the music is out there and you just have to find it. So, to what extent do any of us actually, create anything? Because wouldn’t that contradict the laws of physics? In a way, it’s all out there and it’s just a matter of rearranging the atoms in different forms. I’m sorry, I’m getting very metaphysical here. [Both laugh] I love doing both. I love writing songs and I love arranging songs. The final track on the album, “The Tug of The Moon,” I wrote that song and it’s probably my favorite song on the album – I just love the song – and I look at that and I don’t know how I wrote that. I finished writing the song and I was like whoa.

MM: I found the science behind it in the liner notes very interesting.

SM: Yeah, yeah, all about the gravitational pull of the moon. That song came about because of the leap second we had at the end of 2016. It’s funny with albums because you write them and you record them and then you release them. So, by the time you’re actually out touring them, it’s a couple of years on from the actual creative process. So, in the end of December 2016, we had this leap second and the reason we have it is that the moon’s gravitational pull on the earth not only causes the tides; it’s not just pulling on the water. It’s pulling on the ground as well. You have earth tides as well as water tides. The earth kind of wrinkles and crumples. Only a tiny bit, but it does. The other effect of the moon’s gravitational pull is that it’s tugging on the earth itself and it’s gradually slowing down the earth’s rotation, which means that every hour of every day of every year is a tiny bit longer than the one before it. And in order for atomic clocks to keep pace with the actual position of the sun in the sky, we have to add an extra second to the atomic clocks every now and again so that the sun is still at its zenith every day. Otherwise, it wouldn’t be. If you just let atomic clocks run, it would be noon at the wrong time.

MM: Very interesting! So, you used to do music journalism and were even an editor. What publications did you work for?

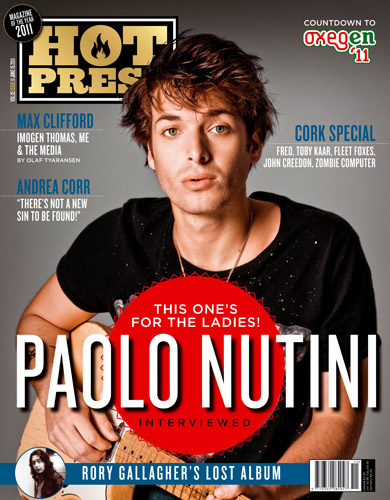

SM: I did music journalism mainly for two publications. Hot Press [is one], which is kind of Ireland’s equivalent of Rolling Stone, it’s a large format magazine – it’s actually gotten smaller over the years I think it’s about the size of a regular magazine now, but it used to be kind of big like Rolling Stone and also like Rolling Stone it was mostly a music magazine, but it had a lot of political stuff as well. The nice thing about writing for Hot Press [was that] I wrote reviews for them but I also would write long profile pieces where I had a big word count to work with and they’d send me off to do an interview really interesting people. I got to interview Jah Wobble and Alison Krauss. I did a really long interview with Alison Krauss, which was just great. So, that was really good for meeting artists. It was a great education, really. And then the other great education was that I also wrote for a daily newspaper. That was a really different animal. With the magazine, I had the luxury of time. But the newspaper would send me to review concerts and I’d have to go to the concert and get home and I had half an hour to get my review written, and file it online so that it could run in the next day’s paper. That was a good education, too, in working under pressure. And when you’re writing journalism, it’s still creative. It’s not fiction and it’s not a song, but you have to put words together that have meaning and that can paint a picture for people. When you write a review, you’re trying to answer the question, what was it like for somebody who wasn’t there? Should I try to go to them? There’s a critical element because you’re answering should you go and see this, too, but you also have to describe it as well and say what it was like. It was a challenge. I’m kind of glad I don’t do that anymore. It took me a long time after I stopped being a journalist to be able to go to a concert and actually just enjoy the music and not be evaluating it while I was listening, and not trying to put words together about it and find a way to describe it. Because you’re trying to reduce this experience into a hundred and fifty words. That’s not easy. And you can’t convey the whole experience in that short little amount of words. So, basically, when you’re attending an event, and you know you have to review it, you’re reducing it in your head. You’re trying to reduce that experience into a few words. So, it’s kind of nice now that I can finally go to a concert and just let the whole thing wash over me and experience the whole of it without trying to reduce it, but that took a long time.

MM: I get it. Because I do some concert reviews and I don’t quite enjoy it as much. I love it when I can afford a ticket and go to a show and not have to worry about any of that.

SM: I hear you. That was my world. Because, being a reviewer, the main reason I did it – God knows it wasn’t for the money [Both laugh] – [is that] it got me into concerts and it was just amazing. I got to go to so many concerts and to hear so many legendary artists that there is no way I could’ve afforded a ticket to go and see. I got to go and see Tina Turner and James Brown, David Byrne from Talking Heads. Those are the names that spring immediately to mind, but all kinds of music legends. And sit up front. You get good seats when you’re writing a review so that’s great, too.

RANDOM QUESTIONS:

MM: Are you currently binge-watching anything?

SM: Yeah, Person of Interest. Only I was in the process of binge-watching it with my husband and kids at home and they’re continuing with it while I’m away, which I’m really cross about because I don’t get to catch stuff until I get home. But it’s so good. We actually bought all five series on DVD. So, we’ve been watching like two episodes every night. We used to read to the kids every night and then they got to be teenagers. We don’t really read aloud anymore, but we got into binge-watching together as a substitute for reading aloud to them an hour before they go to bed. We’ve been through the entirety of Star Trek just before this. We started watching with the original series with Kirk and Spock and everybody and then we went through The Next Generation and Deep Space Nine and Voyager. And we actually finished with Discovery and now we’re like, oh, man, there’s no more Star Trek? There must be more! [Both laugh] Then we started Person of Interest, which is entirely different than Star Trek but still very good.

MM: What’s the first album you ever bought with your own money?

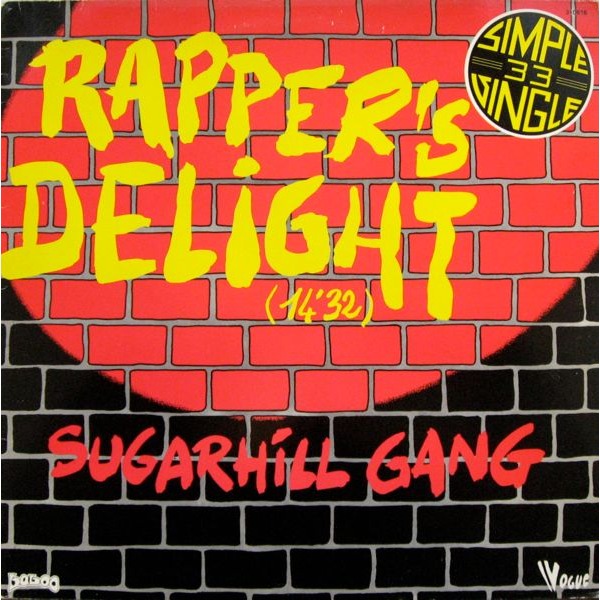

SM: It was “Rapper’s Delight” by the Sugar Hill Gang. It’s not an album, it’s a 12” single, but it was “Rapper’s Delight” by the Sugar Hill Gang. It was the first record I ever bought. I still have it.

MM: What song is stuck in your head right now?

SM: What song is stuck in my head right now? I’m trying to think. What did I wake up with this morning? It was something by Bruce Springsteen. I’m trying to think what it was. [Someone with her says something] It could’ve been “I’m On Fire.” Martin’s saying it was “I’m On Fire” by Bruce Springsteen. I don’t know why it was in my head, but I woke up and I thought, why am I humming that?

MM: Last question. If someone was giving you a million dollars to give to charity and it all had to go to one charity or cause, which would you give it to?

SM: Let me think… Cleaning up oceans!

http://www.facebook.com/sarahmcquaidmusic

http://www.twitter.com/sarahmcquaid

http://www.instagram.com/sarahmcquaidmusic

http://www.youtube.com/sarahmcquaid

http://sarahmcquaid.bandcamp.com

Buy If We Dig Any Deeper It Could Get Dangerous on CD from Amazon

Download If We Dig Any Deeper It Could Get Dangerous on mp3 from Amazon

Leave a Reply